Getting closer to understanding mechanisms behind GWAS signals

Linking disease-associated genetic variants with single-cell RNA abundance

In the last two decades, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) unlocked thousands of genetic variants that are associated with human disease. The biggest promise of these discoveries was a deeper understanding of mechanisms driving disease risk, which would enable more accurate drug target detection. Linking variants to genes and mechanisms isn’t an easy task, as most of them are located in the non-coding genome and they are strongly correlated with neighboring variants (due to linkage disequilibrium), making it hard to pinpoint the causal one.

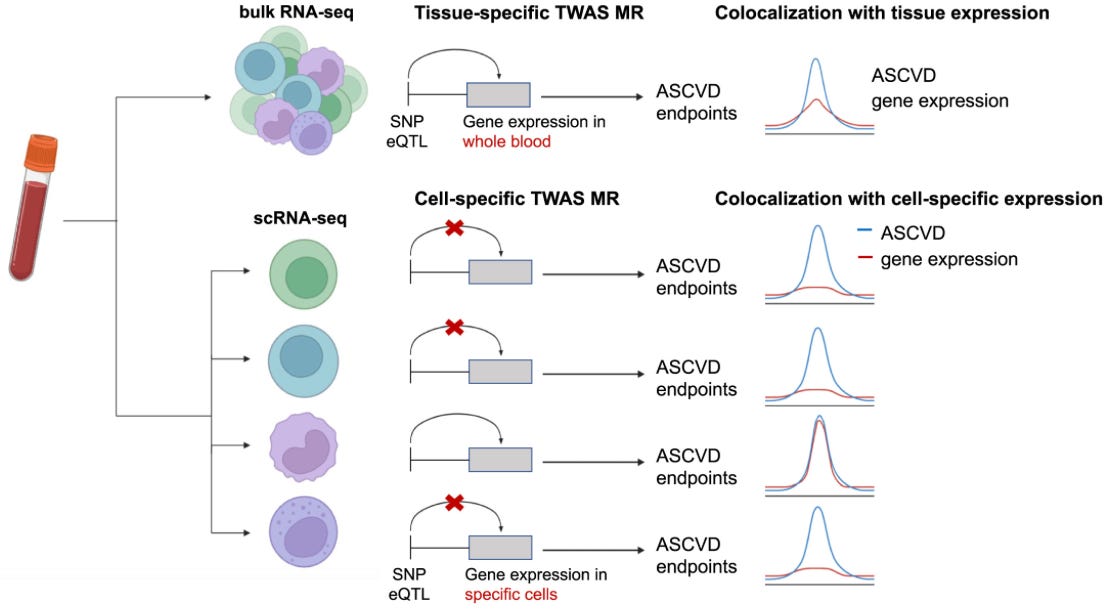

A common theory is that most of these variants alter gene expression. Several initiatives aimed to quantify the effects of genetic variants on RNA abundance in human tissues. The classical example is GTEx: a consortium of 54 biopsied tissues from ca. 1,000 donors that enabled the discovery of genomic loci linked to tissue RNA levels, so-called expression quantitiative trait loci (eQTLs). Merging eQTL data with disease GWASs enabled transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS), where we test if effects of variants on gene expression underlie some of the disease associations.

Most eQTL data come from bulk RNA quantifications in whole tissues. However, gene expression is regulated at the cell level and not the tissue level. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq), a.k.a. quantifying RNA abundance within individual cells, might unlock the potential to link genetic variants with gene expression at an individual cell level. While some first results in this space show very promising results (including our own work on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease), scRNAseq remains a very expensive technology limiting the scalability of such approaches.

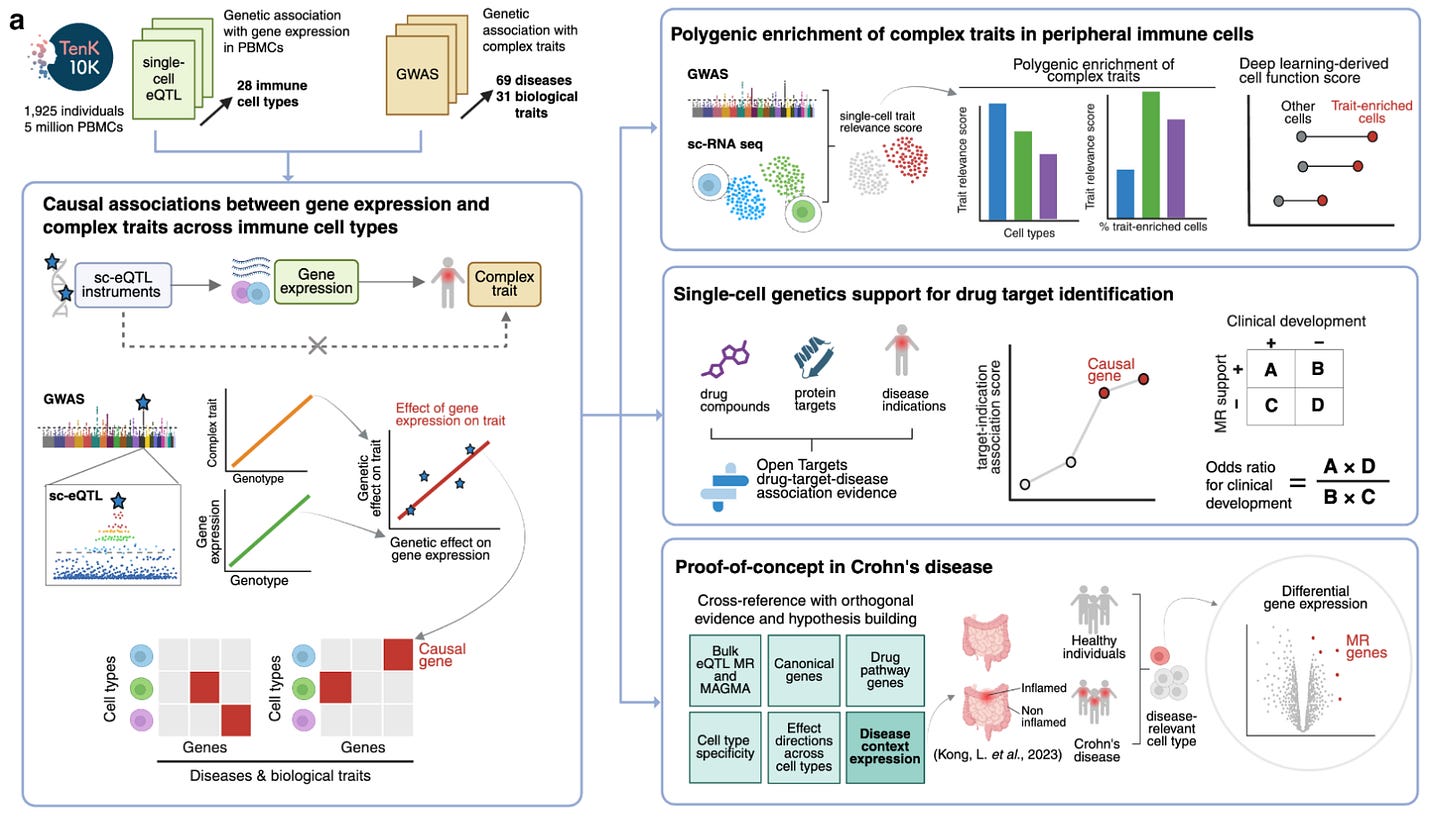

One of the most promising initiatives in this arena is the TenK10K project, which aims to collect 50 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 10,000 participants and perform scRNAseq and whole genome sequencing in all of them. The short-term goal is to link genetic variation with gene expression in a meaningful sample size. The long-term goal is to provide explanations for the mechanisms of action of individual disease-causing variants. Last week, the consortium published a study with the first wave of these results. It’s a study on 1,928 individuals and single-cell eQTL data from 28 peripheral immune cells. The authors linked single-cell eQTLs they detected before to 69 diseases and 31 biological traits from other GWASs. To do this, they used Mendelian randomization.

The study has a number of interesting findings:

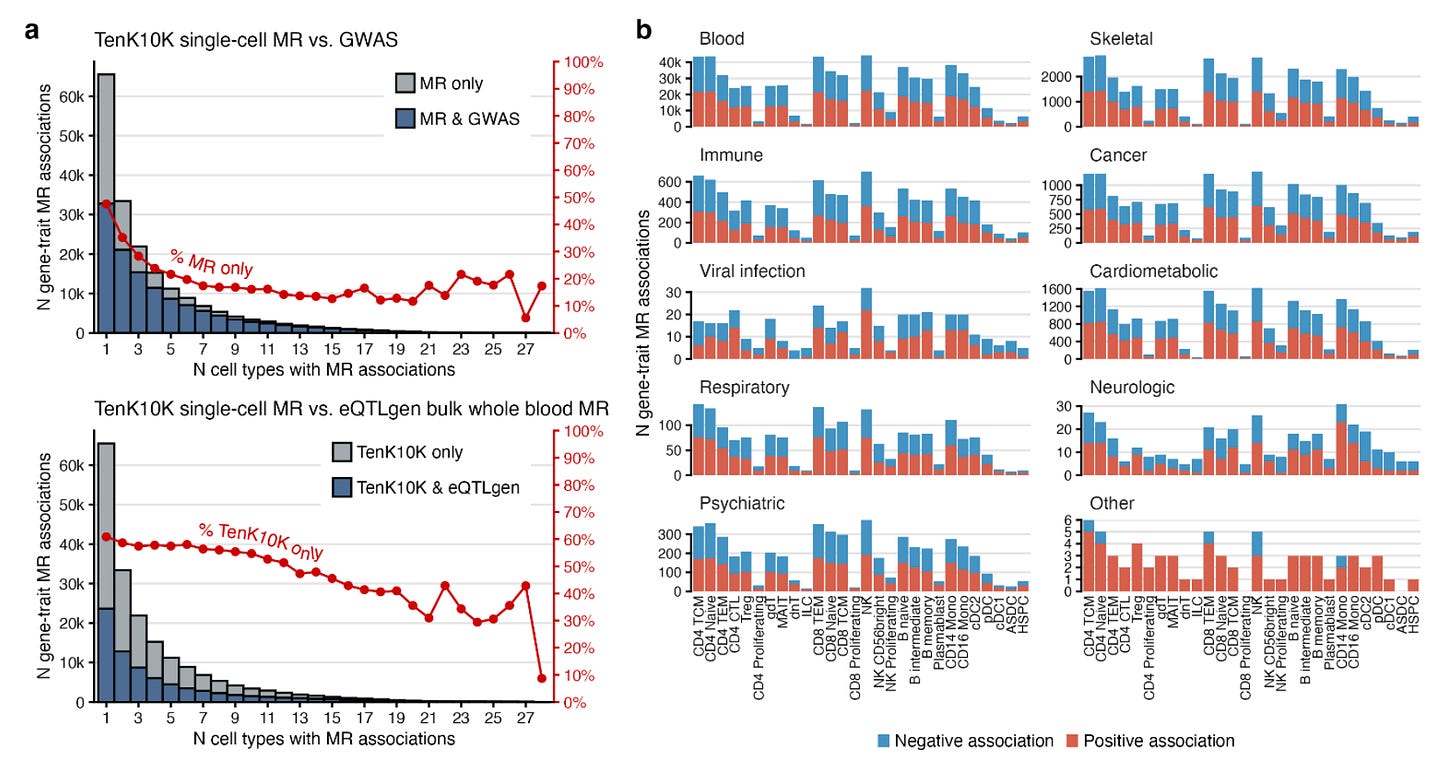

They found a total of 58,058 associations between genetically proxied cell-specific gene expression of 8,672 genes with 53 diseases and 681,480 associations for 16,085 genes with 31 biomarkers. These associations spanned all 28 tested immune cells.

This approach significantly outperformed the use of bulk eQTL data. Despite offering a 15 times larger sample size (N=31,684 in the eQTLGen consortium vs. 1,928 in the current analysis), bulk eQTL-based Mendelian randomization would have missed 61% of the detected associations

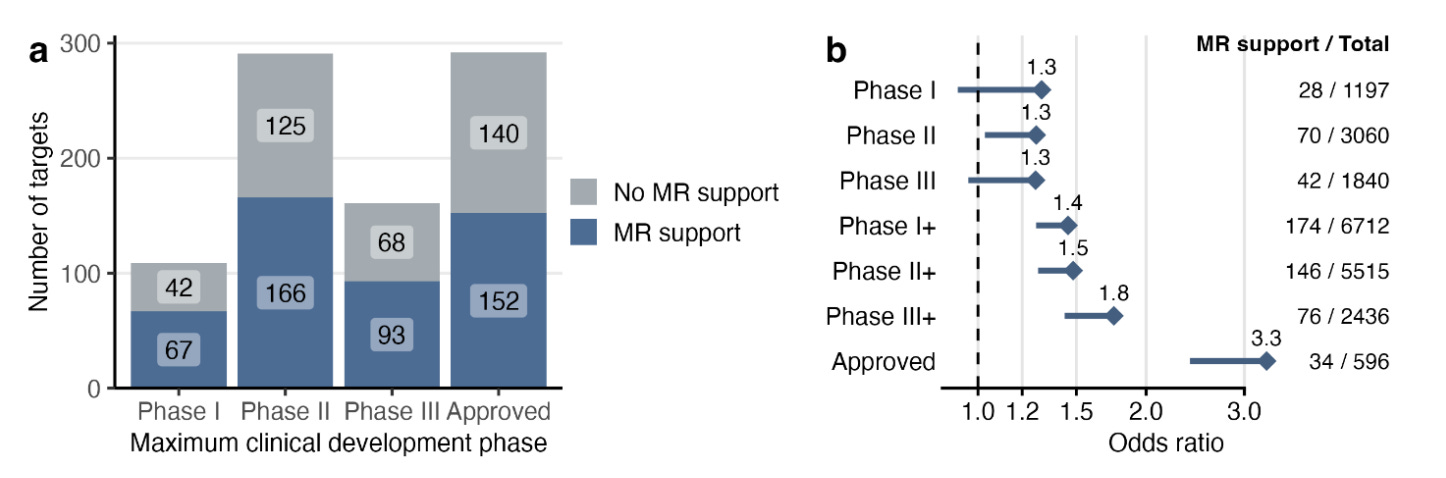

The protein-coding gene-disease pairs with evidence of association in at least one cell type were enriched as drug target-indication pairs across phases of clinical development.

The authors intergrate the cell-specific Mendelian randomization results with data from single-cell RNA sequencing from colon biopsy tissues from patietns with Crohn’s disease and controls. They show some concordance between genetically proxied cell-specific expression linked to disease risk and differential expression of these genes in the same cell type in patients vs. controls.

Why is the study important?

First, it offers a framework for bridging disease-associated variants to single-cell RNA expression. I foresee that bridging sc-eQTL data with disease GWASs is going to become a mainstream follow-up analysis of genomic projects. It is a scalable approach for interepreting GWAS findings.

Second, it provides further support for the theory that searching for cell-specific expression effects can ultimately improve our understanding of the genetic variation driving disease risk. This has the potential to unlock similar initiatives at the tissue level.

Some aftermath thoughts:

I assume many of the detected signals to be driven by pleiotropy due to neighboring genes, thus representing false positive associations. If we aim for higher specificity, adding an additional layer of analysis to overcome this issue, e.g. colocalization, could offer higher confidence for fewer but more likely causal signals.

I still haven’t seen an approach trying to go around, what I call, acting cell pleiotropy. Many of the eQTLs act in a cell-agnostic way, influencing gene expression across multiple cell types. On such occasions, the challenge might not be in detecting the causal gene, but the causal cell. It is a kind of horizontal pleiotropy that we still have no way of addressing. This can be of particular relevance for those interested in cell-tailored therapeutics.

Link to the study preprint: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.28.25334614v1